After learning about the Cambodian Genocide, I’ll pose an exceedingly morbid question.

If something ghastly and horrifying happened to your family, would you hope that people knew about it?

Would you hope that people cared enough to rally for justice on behalf of your family? Would you wish fervently that your family would be remembered? And would it be important that people knew that your family was taken from this earth way before their time?

My immediate family isn’t wealthy or famous, but they’re everything to me. They are my reason for living. I think one of my greatest hopes in becoming a writer is that through my writing, my family is remembered.

I want people to know that my father worked his hands to the bone for us. That my mother’s ability to love was nearly transcendental. That my husband is proof that men of honor still exist. That his family represents case in point why immigrants matter. That my son, my wonderful, perfect two-year-old son’s smile will always be the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen in my life.

And then I put myself in the shoes of those living through the Cambodian Genocide, and it guts me.

It is a matter of sheer chance that my son sits and plays happily on the floor in front of me each day, while another boy at his age was killed in Phnom Penh for ‘sport’ during the Genocide.

Do I write this poetically using metaphors? Or do I write the truth? Because the truth is that during the Cambodian Genocide, babies were taken from their parents, held by the ankles, and smashed against ‘The Magic Tree’ until death.

We can’t just dance around that.

The History of the Cambodian Genocide.

It’s estimated that over a million and a half Khmer people were savagely killed during the Cambodian Genocide which lasted from 1975 to 1979.

The history can be a little complicated, but I’ll fill you in anyway. Cambodia had been dealing with a Civil War around the time of the Vietnam War. During that time, the United States bombed not just Vietnam, but the surrounding areas including Cambodia and Laos. The repercussion of such lasts even to this day.

A charismatic leader, Pol Pot and his henchmen known as the Khmer Rouge used this bombing as a clear-cut example for the need to ‘purge’ all Western influence and to go the Communist route. The majority of his soldiers were child soldiers.

Year Zero.

Pol Pot wished for everyone in Cambodia to work for the ‘common good.’ There would be no more meritocracy. He quite literally re-set the clock to ‘Year Zero.’ Entire cities were emptied and people were pushed into fields to pursue agricultural work. Those who were deemed intellectual were sent to ‘re-education camps’ to learn how to embody the work ethic and values of the ‘common man.’

Intellectuals were also made to answer the commands of rural, common folks who were made to be leaders. The desired impact was that these ‘intellectuals’ would be portrayed as lazy city-slickers without a hard working bone in their bodies. It would be the duty of the formerly downtrodden to ‘re-educate’ them. ‘Intellectuals’ included those who were teachers, doctors, lawyers, and so forth, but also even just people who wore glasses.

A Nightmare.

The conditions in the fields were brutal. There was not enough food and no doctors to treat the illnesses that were rampant among the people. As a result, there was mass starvation and death by disease. Sexual abuse, physical abuse, humiliation, torture, rape, and separation of families were all very common as well. Even as masses of people perished, Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge continued their mission, which at this point, had no real objective. Pol Pot was literally unhinged and began letting people die and having people killed because he imagined them as his adversaries.

Killing Fields of Phnom Penh.

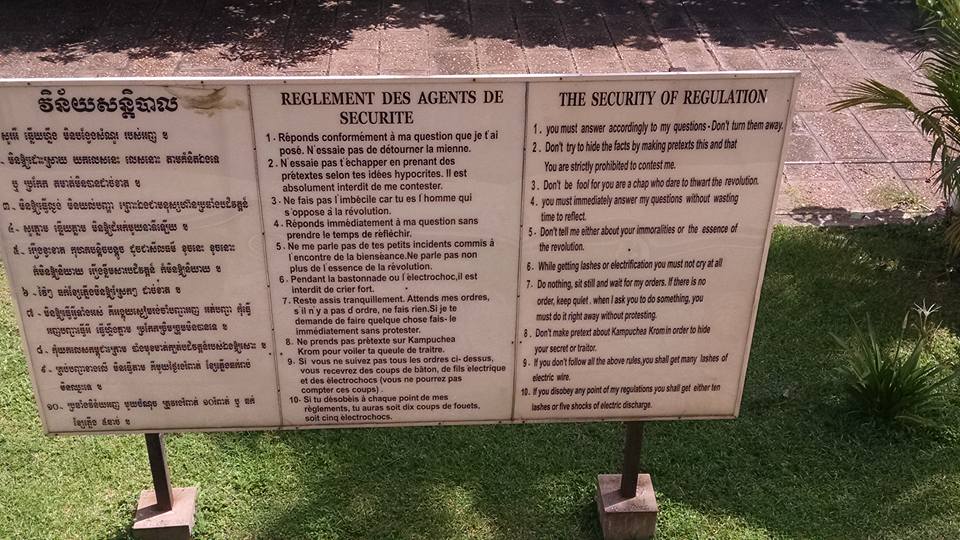

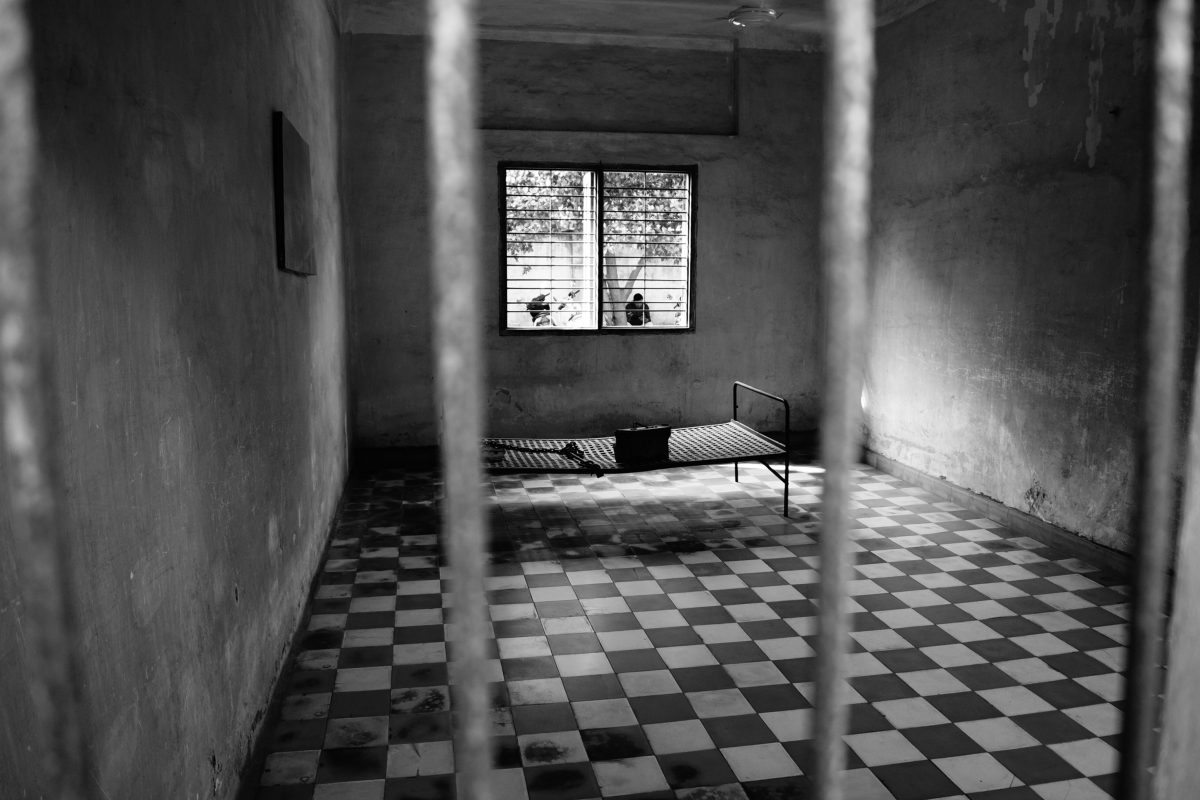

While some perished from the inhumane conditions of the fields, many were sent to actual killing fields. Those sent were ‘interrogated,’ which actually meant they were tortured into confessing something that was untrue. Drownings, lashings, and electrocution were common. After Khmer Rouge soldiers extracted a confession, their killing was then “justified.”

Victims were shot or smacked with bamboo sticks hard enough to sever their spines. Afterwards, they were buried in shallow mass graves. During my visit in 2016, those graves were still very shallow. We went to the Killing Fields on a rainy day and even with the dirt receding just a little, the bones from the victims in the shallow graves re-surfaced. The stench of death and decay is still lingering and present.

There are boards showcasing many of the victims who died at the Tuol Sleng prison. How can I possibly describe the feeling of staring into the dark, terrified eyes of those people? Jarring? It’s at this moment that I realized that this isn’t a Hollywood horror, crafted in a writer’s room in LA. This was real life. And the most stunning realization? Besides the difference in language and maybe some facial features, none of those women were any different than me. Their children were not different from mine. The love for their kids and parents was not, in any way, different than mine.

A Pivotal Moment.

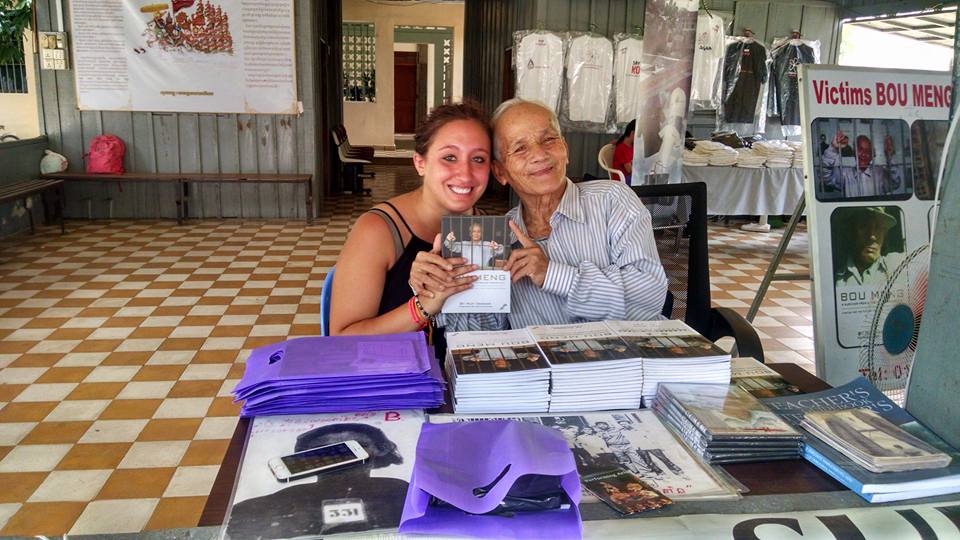

I had the honor of meeting with a genocide survivor who was selling his book in the courtyard. (The killing fields and prison are now a museum — I probably should have mentioned that.) He went on to tell me that his daughter and wife were killed in the prison, and that he’s not sure why, but he survived. The man was fairly frail, and had a tight smile. Unable to control myself, I wept and I hugged him tightly saying, “I’m so sorry” over and over again. I can’t remember his words exactly, but he urged me to live my life and to do so with happiness.

How do you go on living after a Genocide? After the murder of everyone whom you love? How do you not lose your mind knowing that on the other side of the world, most people don’t even know about the Cambodian Genocide?

Meeting this man was an enormous blessing, but also an experience which haunted me. That was until I returned to work the following fall. I’m a public school educator who teaches English, special education, and now, humanities. I was uniquely situated to bring everything I’d learned in Phnom Penh into the classroom. I had our school order books and created an entire English unit around studying the memoir First They Killed My Father.

Working to Keep the History Alive and Remember the Victims.

A few years later, I worked with a colleague to develop our school’s humanity course and curriculum. We highlight not only Cambodia, but countries and nations whose history is often overlooked in the traditional school curriculum. We teach about the impacts of colonialism in Nigeria, the Iranian Revolution and the US’s role in it, the impacts of wealth disparity in Colombia, and much, much more. (Read more about that here!)

I’m confidant that our students in Queens know a great deal about the world when they leave high school and go out into it. They’ll certainly know more about the Cambodian Genocide than their peers who maybe learn about it from a slideshow one day of the year.

Since my visit to southeast Asia, hundreds of students have learned about the Cambodian Genocide in a dignified way in my classroom. That wouldn’t be happening if I never visited Cambodia.

Travel has rippling effects that go way beyond providing a reprieve from work or beautiful photographs. It provides opportunities to learn and to pass that information on to others. It allows people to form genuine connections with different types of people and thus feel motivated to stand up for those people and tell their stories.

0 comment